David Cameron could be forgiven if he enters the Tory

Conference week thinking about his place in history. This, after all, is a man who doesn’t have to

win another election, since he’s given himself a final term firewall against

any future electoral catastrophes. Not

only that, but he’s been able to witness Big Bad Jezza Corbyn’s utter

catastrophe of a party conference over the past week, with possibly only a few

hours off to mull over the deteriorating quality of western foreign policy

(currently sub-contracted out to the country formerly known as the Soviet

Union).

David Cameron could be forgiven if he enters the Tory

Conference week thinking about his place in history. This, after all, is a man who doesn’t have to

win another election, since he’s given himself a final term firewall against

any future electoral catastrophes. Not

only that, but he’s been able to witness Big Bad Jezza Corbyn’s utter

catastrophe of a party conference over the past week, with possibly only a few

hours off to mull over the deteriorating quality of western foreign policy

(currently sub-contracted out to the country formerly known as the Soviet

Union).

Corbyn is a delight in many ways. He’s not quite as different as a party leader

as some hopefuls are suggesting, admittedly.

George Lansbury and Michael Foot were also bizarre lefty true-believers

with a lofty disdain for practical politics, and both proved electorally

disastrous for the Labour party, albeit from a better intellectual vantage point

than the fuzzy minded Corbyn. But Corbyn

is the first of that mould to appear in the age of constant media, and his disdain

for the “media commentariat”, coupled with his notoriously badly structured,

dull black holes of speeches have all gone to contribute to the carefully spun

image of a man who is “authentic”.

Corbyn’s conference was a sheer joy for David Cameron. The Labour leader’s select-a-policy style,

and his refusal – or inability – to have his shadow cabinet speaking from anything like a single song-sheet, must all be making the current leasee of No. 10 Downing

Street giddy with the prospects of his future greatness. And Cameron has to think about his future

greatness as he has no more general elections to win.

What he does have, though, is a referendum to win and if he

is to finally rest on the front bench of Great Tory Leaders (Andrew Roberts

examines the competition in this piece for the Spectator this week) he will

need to ensure that he persuades the country – and much of his own party – to stay

in Europe. Whatever the Euro-sceptics

say, Cameron doesn’t see leaving Europe as much of a triumph for his avowedly

internationalist approach.

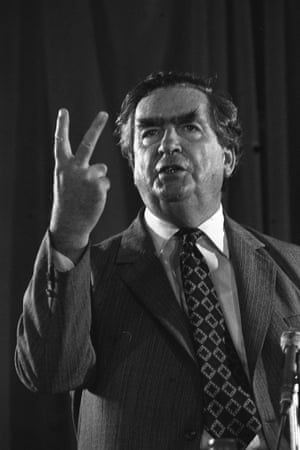

Musing on possible future greatness might have led Cameron

to read more carefully the obituaries of Denis Healey this weekend. Whether great or not – there is plenty of

scope for debate – Healey was one of the best known politicians of his

era. He was an early example of the “celebrity”

politician who could probably be recognised by the average don’t-care-about-politics-they’re-all-liars

voter in the street. Bushy eyebrows may

have helped, and the fact that he was thus easily caricatured by the greatest

performing impressionist of his day, Mike Yarwood, but Healey was also well

known because he was trenchant. He

rarely expressed modest views and wasn’t shy about condemning his

opponents. His reference to Geoffrey

Howe having all the savagery of a dead sheep in his parliamentary attacks has

been well recorded. Less often noted,

and more scathing, was his outraged condemnation of Margaret Thatcher as a

prime minister who “gloried in slaughter” during the Falklands War.

The problem for Denis Healey – who has received universally

positive obituaries – is that his greatest achievement was born out of

disaster. As Labour Chancellor of the Exchequer

during the awful 70s he had to advise a recalcitrant party that the days of

ambitious spending were over. He began –

in the teeth of massive Labour opposition – a sharp programme of

austerity. It was forced upon him by the

fact that he was the first – and to date the only – Chancellor to ask for a

loan from the IMF to tide the tanking British economy over.

I doubt that, when he entered politics after a heroic

military career during World War II, Healey envisaged his claim to greatness

resting on such a terrible reversal of fortunes. He spent the rest of his active political

career trying to persuade the Labour lefties of the need for responsible

policies and a need to appeal to centrist voters. He failed in this.

1 comment:

he election was lost not in the three weeks of the campaign but in the three years which preceded it...in that period the Party itself acquired a highly unfavourable public image, based on disunity, extremism, crankiness and general unfitness to govern.

Post a Comment